Blame Lowell Thomas. He’s as good a person to blame as anyone.

Because if you are going to make a claim—about anything at all—in the forward of a book that goes on to sell tens of millions of copies and remain continuously in print for nearly 80 years, you are going to be responsible for authoring a claim that will stick in the communal mind, that will become a part of how we as a culture think we understand ourselves. And as Lowell Thomas might have put it himself in his folksy manner of speaking, it was a doozy.*

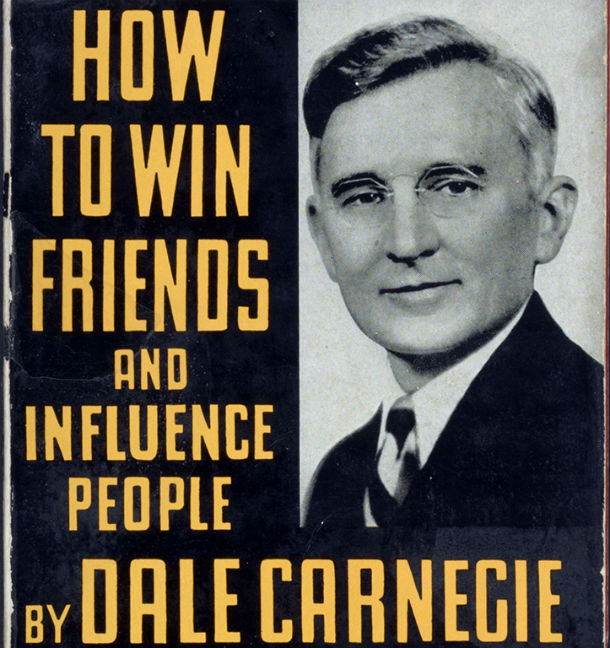

The claim in question comes at the end of his introduction to Dale Carnegie’s “How to Win Friends and Influence People,” the first modern self-help book. His introduction is cinematic in its approach, which makes sense, as Thomas was the newsman to the movie-going public in the 1930s. Thus, the piece reads like a script to a newsreel. Thomas tells the stories of three people who had benefited from Carnegie’s famous public speaking and self-confidence course and then tells the mildly heroic tale of Carnegie himself, the entire tale, from the age of zygote till the present day, in a breezy few pages.

In his college days, we learn, Carnegie was embarrassed by his family’s farm poverty and wanted to come up with something to stand out among his classmates. (Carnegie was born in Missouri in 1888, so this would be 1906 or so at State Teacher’s College, which is now Central Missouri State University. Go Mules!) Because he was neither an athlete nor an actor, he thought he would attract attention as an orator and join the debate society.

Realizing that he had no flair for athletics, he decided to win one of the speaking contests. He spent months preparing his talks. He practiced as he sat in the saddle galloping to college and back; he practiced his speeches as he milked the cows; and then he mounted a bale of hay in the barn and with great gusto and gestures harangued the frightened pigeons about the issues of the day.

But in spite of all his earnestness and preparation, he met with defeat after defeat. He was eighteen at the time—sensitive and proud. He became so discouraged, so depressed, that he even thought of suicide. And then suddenly he began to win, not one contest, but every speaking contest in college. Other students pleaded with him to train them; and they won also.

Thomas leaves out one vital detail: What changed? Suddenly, he began to win. What changed? I want to read on. Picture pages flying off a calendar and then a train and a map of the lower 48 states with a line taking us from city to city. Maybe the picture shifts from black and white to color. Thomas was a movie maker and radio personality and he knew how to make even a quiet intellectual effort—a life spent helping others to gain self-confidence—read like a hero’s journey.

Dale Carnegie claimed that all people can talk when they get mad. He said that if you hit the most ignorant man in town on the jaw and knock him down, he would get on his feet and talk with an eloquence, heat and emphasis that would have rivaled that world-famous orator William Jennings Bryan at the height of his career. He claimed that almost any person can speak acceptably in public if he or she has self-confidence and an idea that is boiling and stewing within.

The way to develop self-confidence, he said, is to do the thing you fear to do and get a record of successful experiences behind you.

At the end, Thomas sums up Carnegie’s gift to the world: “Professor William James of Harvard used to say that the average person develops only 10 percent of his latent mental ability. Dale Carnegie, by helping business men and women to develop their latent possibilities, created one of the most significant movements in adult education.” That is the claim. The word “latent” is the only element connecting those two thoughts. James is one of those figures in American history whose quotes have proved to be very useful for popular writers even when they are taken out of context. Or, especially when they are taken out of context.

To the best of anyone’s intellectual reconstruction, James never said anything of the sort. It is known that he carefully watched a colleague educate his child in an enhanced way with the goal of achieving a superior intellect. (The child had a difficult life.) In nonacademic lectures, that is, lectures delivered to entertain and educate more than to explore ideas, James apparently used to say that human beings use only a portion of their available intellectual energy, that we do not meet our full potential. Which is probably true or perhaps is not.

Decades later, by the time Thomas wrote his sentence—please note that he reports it as something James “used to say”—the thought must have been common. So common that it acquired a specific percentage, ten percent, and shifted from human intellectual “potential” to our brains, our mental ability. We only use ten percent of our thought-thinkers. Everybody knows that. Thomas wrote this to read like an after-dinner speech, which of course is no accident: it is an introduction to Dale Carnegie’s public speaking (and more) book, and everything Lowell Thomas ever said out loud sounded like it was an after-dinner speech, anyway. In Carnegie’s world, and Thomas’, “potential” is everything. It is as American a conceit as anything we Americans ever tell ourselves about ourselves: Live up to your potential. Progress, progress, progress.

Neuroscience is not proving the thought to be correct; the closest one can come to the idea in reality is that our brains are complex and use one-hundred percent of available neurons at all times, that general maps of the brain are generally correct but each person’s brain appears to be unique and possesses fluid boundaries among those general areas, and that we at most pay attention to about ten percent of what our brain is doing at any moment anyway. (I just typed that sentence without paying attention to the location of the keys and while listening to a bird that ought not be outside my window on a cold January afternoon. My brain is humming along quite well without me. I’m not even at ten percent today.)

Earlier in Thomas’ introduction, he mentions that Carnegie has personally overseen and critiqued 150,000 speeches given by people taking his course. The source he gives is “Ripley’s “Believe-It-or-Not.” which is not a source one cites for, well, anything. And Ripley’s source for the statistic was: Dale Carnegie. Thomas continues with even more math: “If that grand total doesn’t impress you, remember that it meant one talk for almost every day that has passed since Columbus discovered America. Or, to put it in other words, if all the people who had spoken before him had used only three minutes and had appeared before him in succession, it would have taken ten months, listening day and night, to hear them all.” Well, okay. That circle of citations citing citations created for the sake of citing them is not a bad thing in and of itself; it’s after-dinner talk logic. It’s logic like that that probably landed us the “ten percent of our brains” idea in the first place. (When giving a speech, use numbers because they sound like facts.)

That “ten percent” idea was presented by one of the great communicators (Lowell Thomas) inside a sales pitch written to persuade readers to buy and read a copy of one of the great instruction manuals about honest, persuasive salesmanship. Eighty years later, we have a movie like “Lucy” depicting a hero using her remaining ninety percent. It has earned almost half a billion dollars since it was released six months ago. The estates of William James, Dale Carnegie, and Lowell Thomas should sue for a cut.

* * * *

*I did not link to the Wikipedia biography of Lowell Thomas partly because it reads like it was written by someone who did not like the late broadcaster, and also because I am a Marist College graduate who spent many hours studying and working in the broadcast studios that were available to me in the Lowell Thomas Building on the Marist campus. Go Red Foxes!

____________________________________________

The WordPress Daily Prompt for January 15 asks, “Let’s assume we do, in fact, use only 10% of our brain. If you could unlock the remaining 90%, what would you do with it?”

* * * *

Please subscribe to The Gad About Town on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/thegadabouttown

Lowell Thomas was one of my childhood heroes. I used to watch “Lowell Thomas Presents” every Thursday night and I dreamed of faraway places. I got to meet him, too, in 1979. That was a huge thrill for me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My senior year at Marist (1989-’90), the Lowell Thomas Building on campus had artifacts from Thomas’ many travels to and through Tibet on display through its halls. As a Communications major, I found my eyes drawn to Thomas’ stuff—his camera, a small portable typewriter—more than to the really ancient Tibetan materials that he had brought back.

LikeLike

I think he created modern journalism. When I was a girl, my hero was T.E. Lawrence. It was through “him” I learned of Lowell Thomas. Anyway, I have a copy of “With Lawrence in Arabia” that I won’t part with. I should have asked for an autograph, but…

Interestingly, the year I met Lowell Thomas, I also saw the Dalai Lama in Denver; it was a stop on his first ever US tour. He did not yet speak English. Those two events made me think if I just stayed where I was, the whole world would come to me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting on the origin of that 90%. I was sold on the concept without ever bothering to look it up :p

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sold is the right word, I guess! Thanks for commenting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dale Carnegie’s books are still selling well at our few surviving major bookstores here and I have read a couple of his books in the past. They were more suited for self-help or motivation. The brain use part is really tricky such that sometimes I wonder whether it might explode if it keeps going on overdrive 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love the Dale Carnegie concepts.

LikeLike

Another interesting article Mark. I haven’t read Mr. Carnegie’s book, but I have seen the results of his course: When I was a freshman in college, there was a young man in my dorm who literally hugged the wall when anyone passed him – turned his body toward the wall, placed both hands against it and fixed his eyes on the floor. Rumor had it he did not eat in the cafeteria the entire first term because he was too shy to ask anyone where it was and how it worked. The wall hugging continued for his entire freshman year.

When we returned to the dorm for year two he was a completely different experience. He looked people in the eye, smiled, shook hands, said hello…. What the heck? Dale Carnegie.

LikeLiked by 2 people