Cave of Stories

The aurochs is an extinct form of cattle that overlapped with humans for tens of thousands of years. It lived in Europe, North Africa, and western Asia; the last one died in 1627. We domesticated it: Our modern-day beef cattle and dairy cows are descended from the aurochs and some of them bear a deep resemblance to the extinct animal. (Picture a bullfight but make the animals taller and more muscular and thus the fight more even.) The reasons for the extinction are the familiar ones and can be summed up as: Humans have enjoyed beef for a very long time.

Early modern humans, homo sapiens, showed up around 100,000 years ago and really started to leave a mark on the landscape around 40,000 years ago. This is deep in our prehistory, and no one knows what our Upper Paleolithic ancestors were thinking. It just appears that thinking is something they were doing.

Awareness is a nice thing to have, and every creature with a nervous system has awareness. Some animals even have a form of memory and the ability to use these memories to their advantage in actions taken in the here and now. Some of us have pets that seem to have better situational awareness than people we deal with every day. Awareness is not thought and the use of awareness is not thinking; they are so close, though.

Consciousness is humanity’s great gift and burden.

By 30,000 years ago—discoveries announced in 2014 are pushing this date further back, to almost 40,000 years ago—our ancestors were painting on the stone walls of their domiciles and meeting places. We do not even know if the spots in what were then and are now caves were homes, temples, some form of market. Stone Age man was not writing things down; writing was many thousands of years in the future. We do not know what early man was communicating or how.

Most of the items found and dated from this period are simple tools—scrapers and blades—but some items have been found that may be tools for making other tools, which is a subtle shift but a huge one. When one is making a tool to make another tool, one is aware of something called “the future.”

The earliest works of art also date back some 35,000 years. Carvings of animals and “Venus” figurines, even a flute made from an antler have been found in different locations. What these represented in early man’s mind is not knowable, but items like these they are not tools for immediate use, like knives or arrows. And then there are the many cave paintings found throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The majority of cave paintings depict animals, animals that were being hunted, like the aurochs, and animals that hunted, like fearsome panthers and bears. The minority of paintings are a sort of declaration of “I am here” that any child would recognize: hand prints.

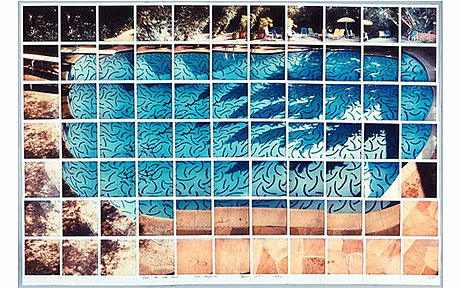

In southern France, the Chauvet Cave is one of the most famous. Rediscovered by modern man in 1994, the many investigations of the many drawings in the cave have narrowed the period in which the works were made to a remarkably specific 30,000–32,000 years ago. (In geologic terms, this is like saying a thing happened in “October” of a certain year.) The picture at top is is of lions hunting aurochs from that cave.

(The cave is the subject of a 2010 documentary, “Cave of Forgotten Dreams,” by Werner Herzog. I believe the film is still available on Netflix, for those with an account. Herzog was given unprecedented access to the inside of the cave, which has never been opened to the public and never will be in order to preserve it. If you are like me and could listen to Werner Herzog read the list of ingredients from a box of breakfast cereal, well, enjoy. It is a great documentary.)

Cave paintings are a snapshot of the birth of human consciousness, and we may be looking at different forms of story on those walls, from journalism to fiction.

The paintings depict animals on the move. Animals they use like horses, animals they hunt, like the aurochs, animals that maybe they avoid, like bears and rhinos.

A fight between two animals is shown. This may be an early form of journalism; the painter or painters saw this happen. The picture at top, of lions on the hunt, demonstrates that the artist or artists had already learned how to effectively use perspective. Some of the lions are in front of other lions, blocking the view of all but the legs of the lions behind them. Their heads are proportionate in size to the perspective used. The cats are not carbon copies of one generic “cat,” but are individual.

A fight between two animals is shown. This may be an early form of journalism; the painter or painters saw this happen. The picture at top, of lions on the hunt, demonstrates that the artist or artists had already learned how to effectively use perspective. Some of the lions are in front of other lions, blocking the view of all but the legs of the lions behind them. Their heads are proportionate in size to the perspective used. The cats are not carbon copies of one generic “cat,” but are individual.

“I saw this” is a form of reporting, is awareness. The birth of consciousness came with the idea of a future. Some of the paintings may depict something like, “You can find this many animals over here, I promise you. Next Tuesday.” Some of the paintings are the first stories, fantasies about a successful hunt or accounts of past ones. Some of them are the first lies: Boasts about the number hunted.

That is where the true birth of consciousness resides, in stories.

____________________________________________

The WordPress Daily Prompt for November 23 asks, “What makes a good storyteller, in your opinion? Are your favorite storytellers people you know or writers you admire?”

* * * *

Please subscribe to The Gad About Town on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/thegadabouttown